Two’s Company. Three’s a Crowd. Five Nanobody® Subunits? That Could Be a New Medicine.

Discovered in camel blood, Nanobody proteins’ small size and combinability are helping scientists reimagine drug discovery.

When a 20-year-old man with a rare genetic disorder walked into a drug manufacturing plant a few years ago, his plea was simple: he wanted their medicine to save his life.

“He wasn't even in our trial. He was literally just waiting for this medicine to get approved so he could take it,” says Rebecca Sendak, Senior Vice President and Head of the Global Large Molecules Research Platform at Sanofi. At that moment, Sendak realized the urgency of innovation.

I looked around the room, seeing all the people at this plant involved in making this medicine listening intently to the story of this future patient. It was just so impactful!

Rebecca Sendak

Senior Vice President and Head of the Global Large Molecules Research Platform

Today, that same urgency fuels Sendak and her team at Sanofi, working on Nanobody molecules. About one-tenth the size of a traditional antibody, Nanobody proteins have a similar ability to bind specific targets, yet can be combined like beads on a string in a mix-and-match approach. Their small size and combinability enable researchers to develop new medicines for complex diseases, where multiple signals and pathways are at work. This flexibility is a dramatic evolution from the dawn of antibody-based therapies.

Antibodies, Their Discovery and Limitations

In late 19th century Germany, the rise of diphtheria and tetanus had researchers racing to find treatments. In 1890, Emil von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato identified the culprit bacteria and tested weakened forms in rabbits and guinea pigs. They realized that the treated animals developed protective immunity. Furthermore, once they transferred the serum from immune animals to others, the recipients became protected, too. The duo hypothesized that blood contained a unique substance – later termed antibodies – that worked like an antitoxin. The field of antibody research was born.

Understanding the structure of antibodies earned Edelman and Porter a Nobel Prize. Later, Köhler and Milstein developed the ability to produce antibodies from immunized animals. This enabled researchers to get pure antibody proteins that could bind to a single, specific target – called a “monoclonal” antibody. This major step towards the use of antibodies as medicines also earned Köhler, Milstein and Jerne a Nobel Prize.

The impact of therapeutic antibodies has since grown, with the advent of molecules that can bind two or even three different targets. As of 2022, more than 162 antibody-based drugs have been approved globally. Yet unique medical challenges remain that go beyond the abilities of conventional antibodies.

“Humans are very complicated, and disease pathology is very complex,” Sendak says. If a disease involves multiple pathways and interactions, scientists may want new tools that can handle more interactions than traditional antibodies allow. “Sometimes you have two different pathways where if you block one, the other pathway just takes over.” A multi-targeting approach can address more complicated biological scenarios, and block both pathways together, for example.

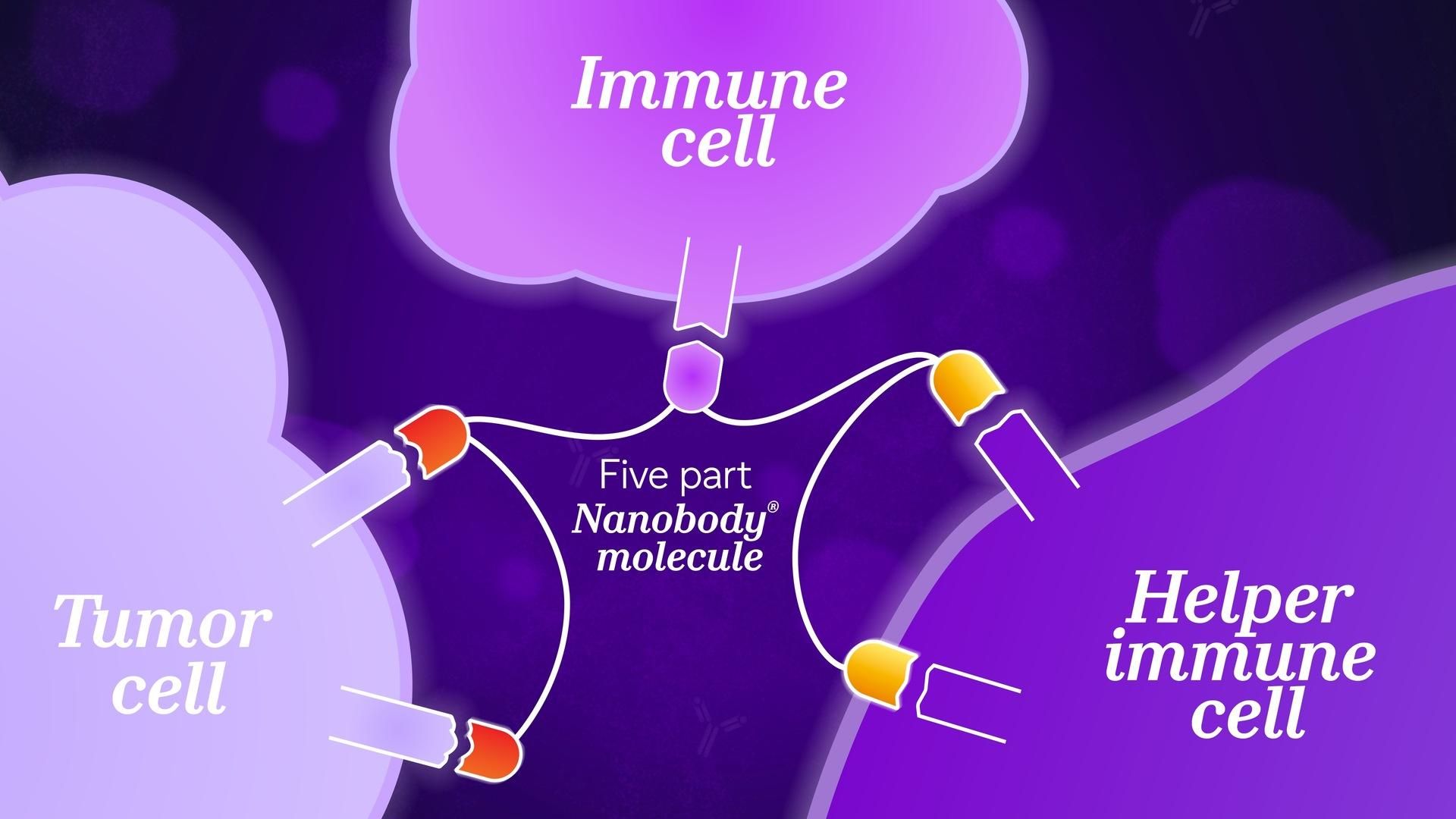

Sendak considers the design of a molecule to help the immune system kill cancer. “You want to first target a cancer cell, bring in an immune cell, and then stimulate that immune cell to kill the cancer cells – these are three different activities.” In this case, the challenge is to physically bring two different cells together and trigger a third activity at the same time. “The geometry of the biology can make this a challenge.” For traditional antibodies, this may be too difficult.

The size of traditional antibodies may also present challenges in designing new therapeutic tools. When researchers combine pieces from different antibodies, “the molecule just ends up getting larger and larger, to the point of being potentially unmanageable,” Sendak explains. Larger sizes may also make it harder for a medicine to reach its intended target. These larger, more complex molecules can also be harder to manufacture.

Scientists were searching for a tool that could fulfill multiple objectives: binding several locations at once, small enough to arrive at their target, and simple enough to reliably manufacture. This search led to the discovery of Nanobody proteins.

Unusually Small and Unique Antibodies

The structural difference between a traditional Y-shaped antibody (composed of heavy and light chains) and a smaller, simpler Nanobody fragment (consisting only of a heavy-chain variable domain).

More than a century after antibodies were first discovered, Raymond Hamers at the Free University of Brussels faced a challenge: he didn’t have suitable experimental material available for students in his lab. In his freezer, he had a blood sample from a camel, that was intended for different research. He decided that he could spare some for his curious students.

When the students identified the camel’s antibodies, “We couldn’t believe it,” Hamers said. Typically, antibodies are ‘Y’-shaped, with two light chains and two heavy chains linked together. The camel blood contained not only the standard antibodies found in most vertebrates, but also a unique, simpler fragment that lacked the light chains. “We spent two years checking whether we were right.” Researchers found these small antibodies in other camel-like species, too, including llamas, alpacas and vicuñas. These small, variable, antibody-like proteins, dubbed “Nanobody” subunits, were seen as having potential use as medicines.

Towards a New, Multi-Valent Therapeutic World

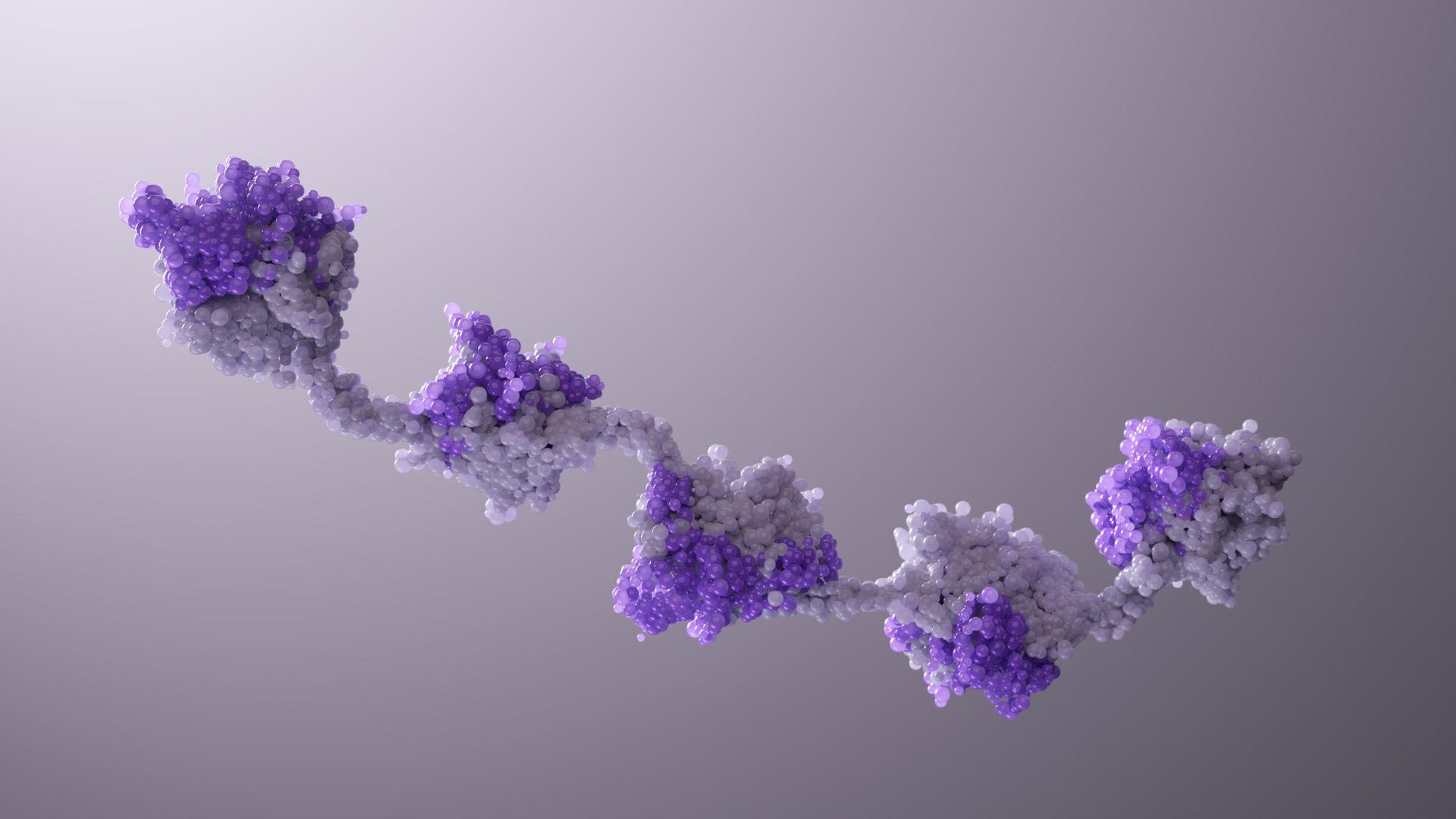

Multiple Nanobody subunits linked together like "beads on a string," showcasing the customizable connectors and flexible linkers. This multi-targeting design is a result of computational biology and protein engineering, involving predictive modeling, synthesis, combination, and rigorous testing.

Nanobody proteins unlock unprecedented flexibility. Described as a “beads-on-a-string” model, a single molecule can be linked to another using different connectors, with their own geometric capabilities. The design is highly adaptable. “Sometimes targets might be far apart, and you need a very long linker. Sometimes they might be close, so you need a short linker,” adds Sendak. This flexibility enables tuning the structure of a Nanobody molecule to different targets and different geometric demands.

Durability is also a tunable property. “Sometimes, you want a substance to hang around the body for a really long time, so that you don't have to dose as frequently. Other times, you might want that medicine to do its job and be cleared away.” While traditional antibodies may circulate for two weeks, Nanobody molecules naturally clear from the body in a few days, unless engineered for a longer stay.

Nanobody Proteins as Medicines

The first Nanobody subunit-based drug, developed by Ablynx (now a Sanofi company), was approved in 2018 to treat a rare and serious blood clotting disorder. Sanofi scientists have built decades of experience working with the technology, accelerating future innovation.

Her team is testing a design that uses seven Nanobody subunits. Sendak says that this degree of multi-targeting is far more advanced than what her team could do when Sanofi first acquired the platform.

We continue to lengthen and push the limits of how many things we can target. It's only possible through trial and error – designing compounds and seeing what works, what doesn't, and how we can do more.

Rebecca Sendak

Senior Vice President and Head of the Global Large Molecules Research Platform

To ensure that Nanobody protein technology works as intended, the Sanofi team takes a cautious approach. They run both positive and negative screens to check whether the molecule has the right features. “You want to see cancer cells die and you don’t want to see activation of some other population,” she explains. To achieve that, Sendak’s team tests different building blocks, their order, along with linker types and lengths, in various permutations. Functional screening tests confirm they’re producing the desired action while avoiding unwanted effects.

A Complex, Computational Future

As more Nanobody subunit “beads” get added onto a “string,” with different linker possibilities, molecular interactions get more complex. The number of possible combinations grows exponentially, to where relying solely on experimental trial and error isn’t always feasible and is highly inefficient. The total design space for complex biologics is massive, and even with all the high-throughput screening capabilities Sanofi has implemented, it is not possible to experimentally test all possibilities. That’s why Sanofi has been integrating predictive, computational tools in its molecule design workflow. “We have a virtual screening approach that can predict how these molecules will bind, as well as other computational methods to ensure the compounds will exhibit suitable biophysical behavior, allowing the compound to be developed as a patient-friendly drug” Sendak describes. By doing so, these computational tools narrow the focus of what to test with physical experiments, helping to shorten development timelines by as much as six months.

For Sendak, it is quite special how one platform has unlocked completely new ways to help patients. “That all of these new tools have that chance to make it out of the gate and benefit patients is just wonderful.”

NANOBODY® is a registered trademark of Ablynx N.V.

Explore More

NANOBODY® Technology Platform

How We’re Redesigning Rare Disease Research

AI Across the R&D Value Chain: Clinical Development

References

- Verheijden, K. L. M. et al. "Antibody challenges: Overcoming limitations in therapeutic antibody development." Current Opinion in Structural Biology vol. 94 (2025): 102766. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2025.102766

- de Quadros, S. L. C. R. et al. "Diphtheria and tetanus toxoid vaccines: a review of the history, development, and current use." Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical vol. 50,1 (2017): 10-19. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0430-2016

- The Nobel Prize (1972). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1972 Press Release. Accessed 29 October 2025. Available at https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1972/press-release/

- Biomol. The Invention of the Hybridoma Technology. Accessed 29 October 2025. Available at https://resources.biomol.com/biomol-blog/invention-of-the-hybridoma-technology

- New Scientist (2007). The camel factor: Nanobody revolution. Accessed 29 October 2025. Available at https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19626241-600-the-camel-factor-nanobody-revolution/

- Al-Hajj, M. A. A. et al. "Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: An update on their mechanisms of action and clinical applications." Frontiers in Immunology vol. 13 (2022): 953526. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.953526