Why Smoldering Neuroinflammation Must Be Part of the Discussion to Improve Care in Multiple Sclerosis

The phenomenon of smoldering-associated worsening in multiple sclerosis has been widely accepted by the medical community, yet much work is needed to fully integrate it into clinical practice. Different kinds of tools are needed to bring smoldering neuroinflammation into the clinic to spark conversations about how disability may progress even in the absence of relapses.1

Tackling smoldering-associated worsening in multiple sclerosis (MS) is an essential part of the future of disease management, as it could help explain the confusing disconnect – why someone with MS might feel their disease is getting worse, even though they have not had a relapse or new MRI lesion in years.

When I talk to people with MS, the idea of smoldering neuroinflammation really resonates with them because this explains biologically what they are noticing – a steady, slow progressive worsening of disease that’s still occurring despite being on therapies that dampen almost all evidence of relapse disease biology.

Jiwon Oh, MD, PhD

Staff Neurologist and Medical Director, Barlo Multiple Sclerosis Program, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto

Dr. Jiwon Oh, Medical Director of the Barlo Multiple Sclerosis Program at St. Michael's Hospital at the University of Toronto, recently joined Luis Felipe Orozco, MD, PhD, Sanofi’s Global Medical Head of Neurology, to discuss how to better incorporate a discussion of smoldering neuroinflammation as part of the MS disease process into clinical practice.

Expanding the Conversation

The tools used in clinical practice today, such as vision charts, tuning forks and reflex hammers, test visual acuity, sensation, strength and other neurological functions, but these cannot easily measure the sometimes subtle symptoms associated with smoldering neuroinflammation, underscoring a critical unmet need in MS. 1

Currently, there are no adequate clinical tools to detect smoldering-associated worsening in practice. Inconvenient or expensive tests including full cognitive batteries may be able to detect the subtle changes caused by smoldering-associated worsening, but such tests are not easily available in most clinical settings. Clinical MRIs are very useful to detect relapse-related disease activity, but these tools have limited ability to identify subtle changes that people with MS experience. For instance, the signs of early disability might present as slight changes in how a person speaks, feelings of fatigue, or the ability to do daily activities, and there may be no changes associated with these symptoms on regular clinical MRIs.1

I began to notice that I couldn’t play my musical instruments like I had been. I could go to a jam and play for an hour, and then my hand would start going dead. That’s weird because I’m the guy that’s always there four hours later still player. Everything just seemed to be slowing down.

Roger

Living with multiple sclerosis

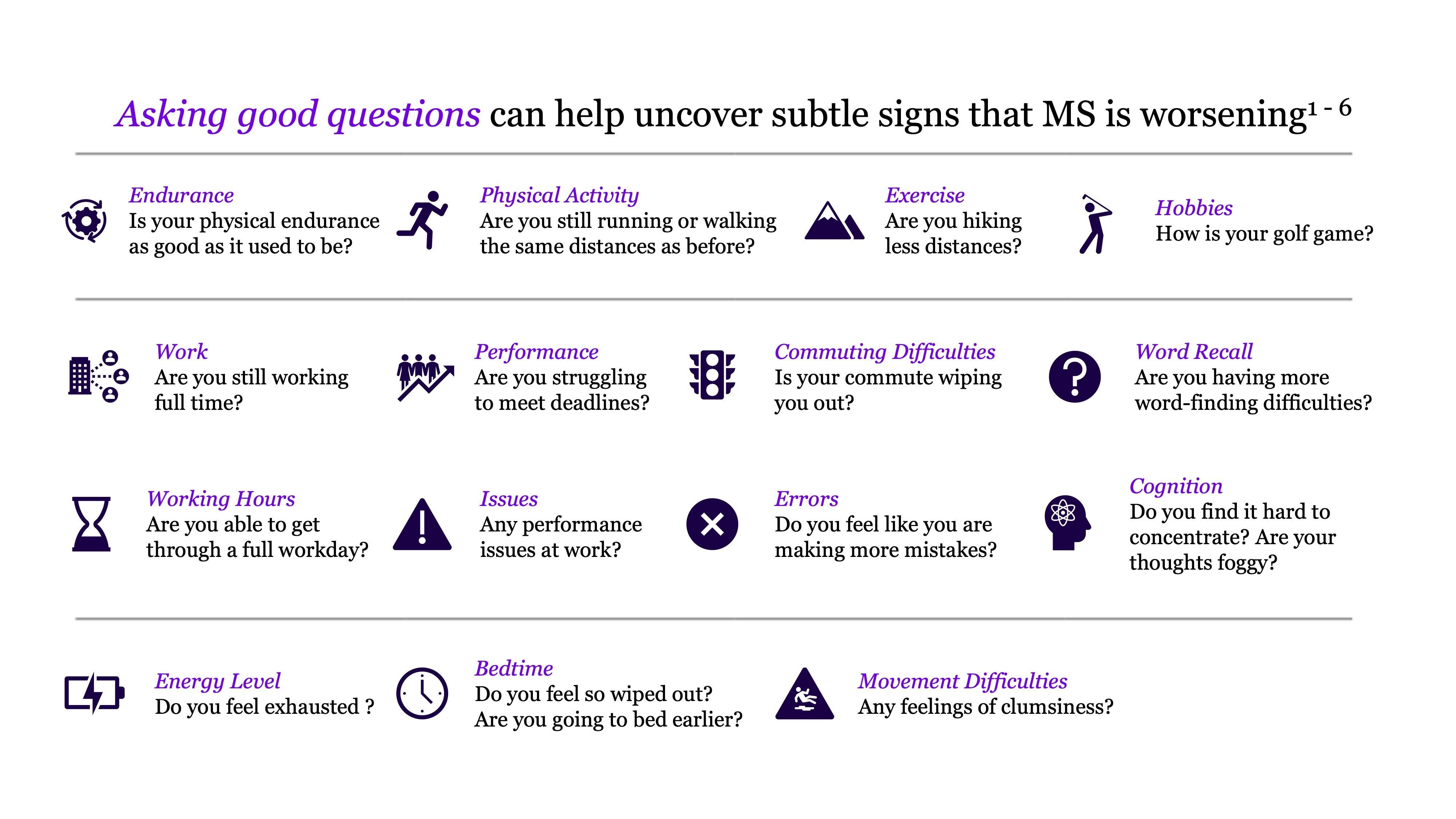

Different evaluation tools are needed to expand the discussion in the clinical setting and enable healthcare professionals to hear from people with MS on how MS is impacting their day-to-day lives and how that impact continues to change over time.1 Asking good questions can help bring to the surface the kinds of problems people are noticing. Otherwise, the more subtle signs of worsening of disease may not be identified in a routine exam.

As technology evolves, the evaluation methods may become more seamless, for instance enabling a mobile phone to measure cognition in the background through speech or typing patterns, enabling disease progression to be tracked in real time.1

Adoption of methods ultimately successful in measuring cognitive decline and more subtle changes in physical abilities will also likely be necessary from the medical community to ensure widespread integration into clinical practice.

A Full Spectrum Disease

In the early stages of MS, both aspects of the disease – the relapsing and smoldering components – are active, but not equally so. What may be surprising is that in people with MS treated with available disease-modifying therapies, when disability occurs, the vast majority of events do not come from relapses, but from smoldering-associated worsening. 1

As the term implies, smoldering neuroinflammation describes the slowly-evolving and chronic inflammatory processes directly linked to innate immune cells like microglia that cause widespread chronic CNS inflammation, activating with other immune cells in the CNS and contributing to neurodegenerative processes. This component of MS remains largely untouched by most current therapies, explaining why disability continues to progress.1

Understanding smoldering neuroinflammation makes all the more evident the need for effective therapies that reach within the central nervous system to address the drivers of neuroinflammation that is underway from the start.

The medical field is closing in on how to detect and potentially treat the full spectrum of disease.

Innovation to Unlock New Doors

Sanofi is leveraging decades of expertise in neurology to advance the next chapter of science in MS.

Sanofi is conducting ongoing research to identify drivers and pathways of smoldering neuroinflammation in MS. Identifying such processes will facilitate new approaches to detect and address smoldering-associated worsening, holding great promise for improving care today and health outcomes for people with MS in the future.1

We know the science is telling us disability is happening for people living with MS, sometimes before it’s detected. A key first step to addressing disability progression is talking about it. When we have these conversations in the clinic, we're understanding more and more how this biological process manifests in their day-to-day lives and what it looks like in the real world.

Luis Felipe Orozco, MD, PhD

Sanofi’s Global Medical Head of Neurology

Since the introduction of the first disease modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis, tremendous progress has been made to advance medical science in the field. Now some thirty years later, more than two dozen different MS treatments are available in many countries around the world, making MS today nothing like the disease of the past.2 Despite this, great unmet needs still remain and the next frontier of MS research will be focused on improving our understanding of smoldering neuroinflammation, exploring innovative strategies to address the full spectrum of disease and help improve patient care through advancements in both treatments and clinical practice management.

Explore More

Neuroimmunology Unlocks the Mysteries of the Brain

A Smoldering Process: A New Way of Thinking about Multiple Sclerosis

The Impact of Multiple Sclerosis on the Brain: A Deep Dive with Sanofi

References

- Scalfari, A, et al. (2024) Smouldering-Associated Worsening in Multiple Sclerosis: An International Consensus Statement on Definition, Biology, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Ann Neurol 2024;00:1. DOI: 10.1002/ana.27034.

- Multiple Sclerosis Foundation (2018). Treatment for MS. Accessed online July 2024.

- Lakin L, Davis BE, Binns CC, Currie KM, Rensel MR. Comprehensive approach to management of multiple sclerosis: addressing invisible symptoms—a narrative review. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(1):75-98.

- Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, de Stefano N, et al. Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2016;263(6):1053-1065.

- Dillenseger A, Weidemann ML, Trentzsch K, et al. Digital biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Brain Sci. 2021;11(11):1519.

- Halper J, Kennedy P, Miller CM, Morgante L, Namey M, Ross AP. Rethinking cognitive function in multiple sclerosis: a nursing perspective. J Neurosci Nurs. 2003;35(2):70-81.