Sanofi has been a leader in vaccines for over 100 years: thanks to our innovative vaccines and global reach, we have helped reduce the burden of many infectious diseases. Across the stages of life, vaccination helps protect humanity from emerging epidemics and helps create and maintain healthy communities moving forward. Whether you're here to explore our cutting-edge research or learn more about vaccine-preventable diseases, you're in the right place.

Vaccines Help Protect Us

Every year, vaccination saves up to 5 million lives around the world. But an additional 1.5 million lives could be saved with improved vaccination coverage.1

Our Vaccines at a Glance

500M+

people vaccinated annually with our vaccines worldwide.2

2.5M

vaccines doses supplied every day.2

€1bn

R&D vaccine investment annually. 2

What’s Next in Vaccines?

Our leadership in immunoscience drives transformative innovation across our vaccine portfolio. This expertise underpins our cutting-edge vaccine research, enabling us to help tackle global health challenges with innovative solutions. Learn how our commitment to advancing immunoscience fuels breakthroughs in vaccine R&D.

Our Latest Stories

December 17, 2025

The Cause of COPD You Don't Know: Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency

Do You Want to Participate in a Clinical Trial at Sanofi?

Explore More

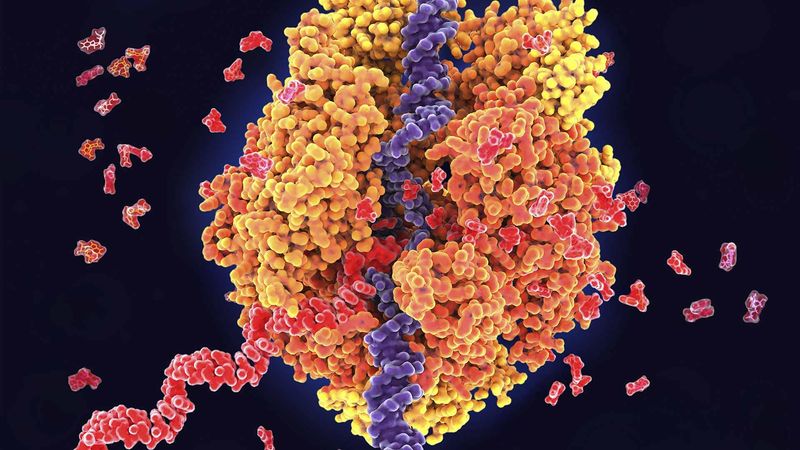

How We Make Vaccines

References

- World Health Organization (2019) Immunization Facts in Pictures. Accessed November 2024

- Sanofi – internal references